If we could look down upon the Earth in the mid-16th century, we would see a world being strangled by an invisible hand.

Welcome to 1545 Global Transformation.

In 1540, Western Europe suffered a drought of the century, with rivers drying up and forests spontaneously combusting; by 1545, however, many regions turned abnormally cold. Summer ceased to feel like summer, and crops lingered between life and death.

- In China, the Henan and Shandong regions saw miles of scorched earth. Harvests failed, prices skyrocketed, and refugees were left wandering the land.

- In the English Channel, the cold, damp weather became a breeding ground for plague. A terrifying outbreak of typhus forced the French fleet into a panicked retreat.

- In Catholic Europe, faced with inexplicable famine, pestilence, and death, the public fell into a collective hysteria. They turned their fury toward imaginary demons, causing the “witch hunts” to reach a fever pitch.

- In the Andes, the brutal climate made the already barren highlands even less productive, yet it led to the accidental discovery of the “Rich Mountain”.

The climate “butterfly” flapped its wings, triggering a series of global storms.

Catalogue

- The Americas’ 1545 Global Transformation: The Silver “Gates of Hell”

- The Europe’s 1545 Global Transformation: Brutal Naval Battles and Religious Fire

- The Asia’s 1545 Global Transformation: Shocking Night Raids and Shadow Empires

- The Terrifying Scientific Seeds of the 1545 Global Transformation

- Conclusion: A World Irrevocably Tied Together

The Americas’ 1545 Global Transformation: The Silver “Gates of Hell”

In April 1545, high in the Andes at 15,700 feet, the wind whipped snow like a knife against the skin. An Indigenous man named Diego Gualpa was searching for his lost llamas when he tripped and fell into a shallow pit. Cursing as he pushed himself up, his hand brushed against a heavy stone. In the dim light, he saw a strange, metallic, greyish-white luster. He brought the rock back to his camp on a whim.

When Spanish colonials saw the stone and cracked it open with a hammer, a cry went up: “My God…”. The interior revealed a vein of nearly pure, silver-white metal.

The news spread like wildfire across the Andean plateau, leaped over the Atlantic, and drifted into the halls of Charles V. Overnight, Potosí—a place whose very name breathed desolation—became the hottest “Rich Mountain” on Earth. Thousands of colonials, adventurers, and desperados flooded in, driving the Indigenous population into the “Gates of Hell”.

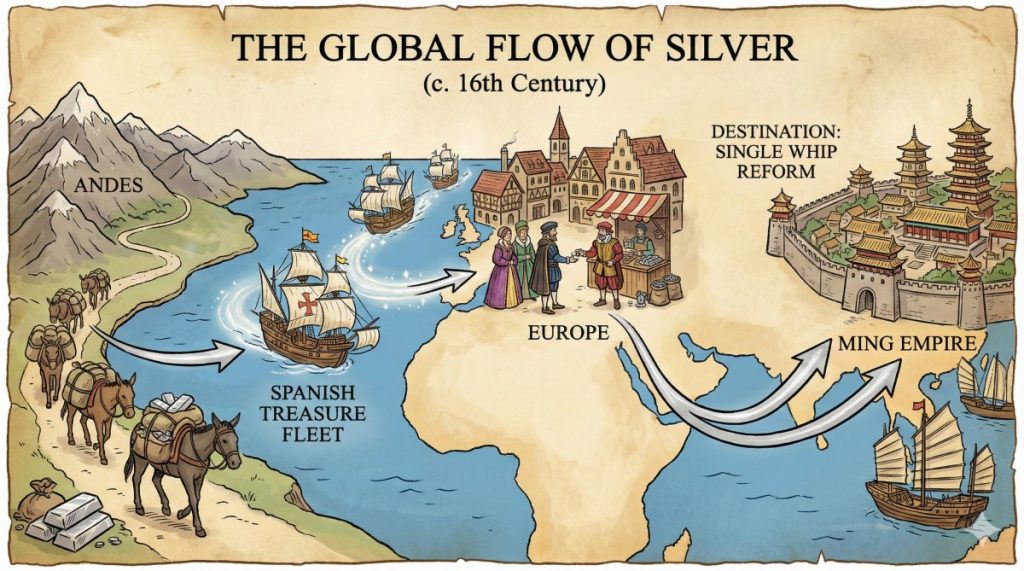

But above the mines, the silver flowed like a spring. It was minted into coins, loaded onto mule trains, hauled over the Andes, and shipped across the Atlantic in “treasure fleets” to fuel Charles V’s wars against France, the Ottomans, and Protestant princes.

This silver flooded the markets. It stripped the value from the savings of old-world landlords but sent prices soaring, allowing savvy merchants to fill their pockets. Finally, the silver sailed to the Far East, flowing into the veins of the Ming Empire.

While it brought silk, tea, and porcelain to European aristocrats, it also enabled the “Single Whip Law”, effectively buying the Ming Dynasty more time on the historical stage.

The Asia’s 1545 Global Transformation: Shocking Night Raids and Shadow Empires

As religious fires burned in Europe, Asia was dealing with its own fractures.

In May 1545, the siege of Kalinjar Fort in India reached its climax. The Afghan warlord Sher Shah Suri—the man who had routed Humayun five years earlier—was on the verge of victory when a gunpowder explosion accidentally claimed his life.

Though he ruled for only five years, his legacy was immense: he unified the currency with the silver Rupee, standardized weights and measures, and built the Grand Trunk Road to connect India. His death left a power vacuum that his successors couldn’t fill.

Meanwhile, the exiled Humayun, backed by the Persian Safavid Dynasty, stormed back into Afghanistan in November 1545, reclaiming Kabul and reuniting with his three-year-old son, Akbar.

In China, the Ming Empire drifted under the “Taoist shut-in” rule of the Jiajing Emperor.

But Altan Khan was doing more than raiding; he was building a “Shadow Empire” in the steppes. He attracted Han Chinese farmers and craftsmen to build houses and temples, transitioning his people toward a mixed agricultural-nomadic economy. The Ming frontier was as precarious as a stack of eggs.

At the same time, along the southeastern coast, with the intensification of the sea – ban policy, smuggling trade along the coasts of Fujian and Zhejiang provinces became as rampant as a wildfire out of control. In just a few years, it would escalate into a serious “Japanese pirate chaos“(WoKou), which was like a ticking time – bomb that finally exploded, causing great turmoil in the region.

In Japan, the Battle of Kawagoe changed the fate of the Kanto region. The Hojo clan, led by Hojo Ujiyasu, faced a massive coalition of 80,000 men with only 8,000 of his own. In a daring night raid, Hojo’s “light-armored suicide squad” sliced through the coalition’s camp like a hot knife through butter. The victory secured Hojo dominance over Kanto for the next century.

The Terrifying Scientific Seeds of the 1545 Global Transformation

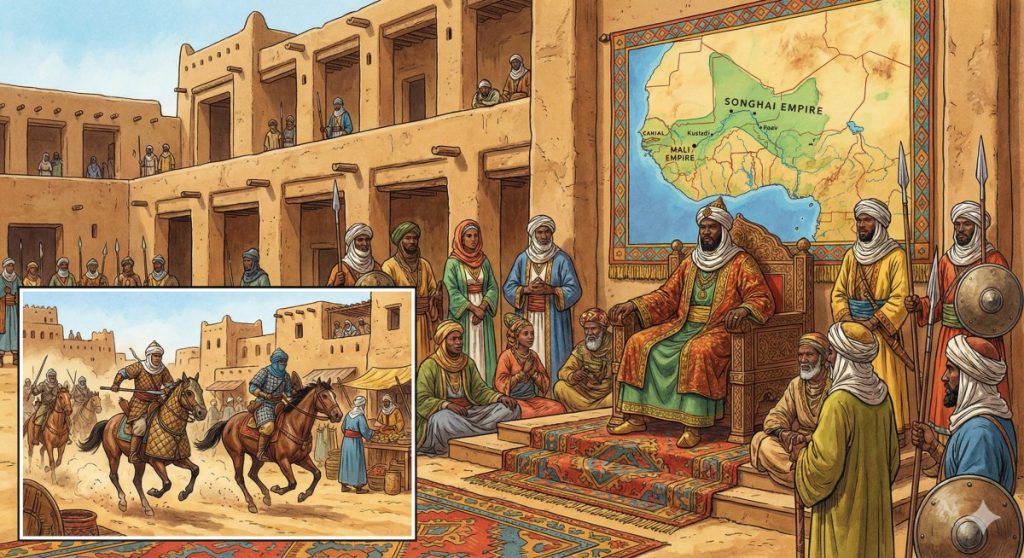

Turning our gaze away from Eurasia toward more distant continents, we find the Songhai Empire at its zenith in West Africa.

King Askia Ishaq I was a formidable force; this year, he led his armies into the capital of the former hegemon, the Mali Empire. Mali’s era as the dominant power of West Africa came to a definitive end, leaving Songhai as the undisputed supreme authority of the Sahel region.

However, the struggle for ownership of the Taghaza salt mines between Songhai and the Saadi Dynasty of Morocco to the north reached a fever pitch. Ishaq I dispatched 2,000 elite cavalry to raid trade towns within Moroccan territory.

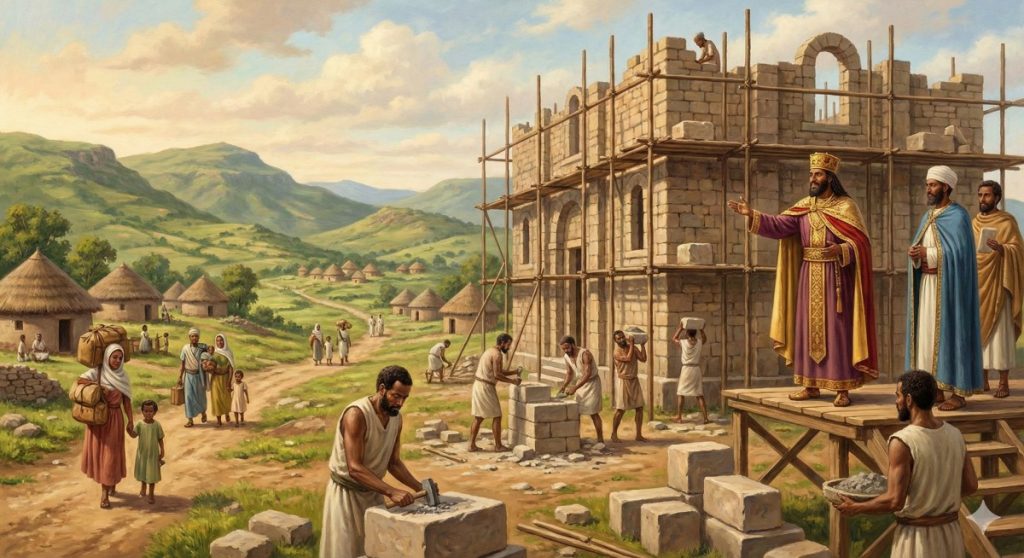

In East Africa, Emperor Galawdewos of Ethiopia took advantage of the power vacuum following the death of Imam Ahmad of the Adal Sultanate. He began reclaiming lost territories piece by piece, rebuilding churches, and unifying his people. This ancient Christian kingdom exhibited remarkable resilience.

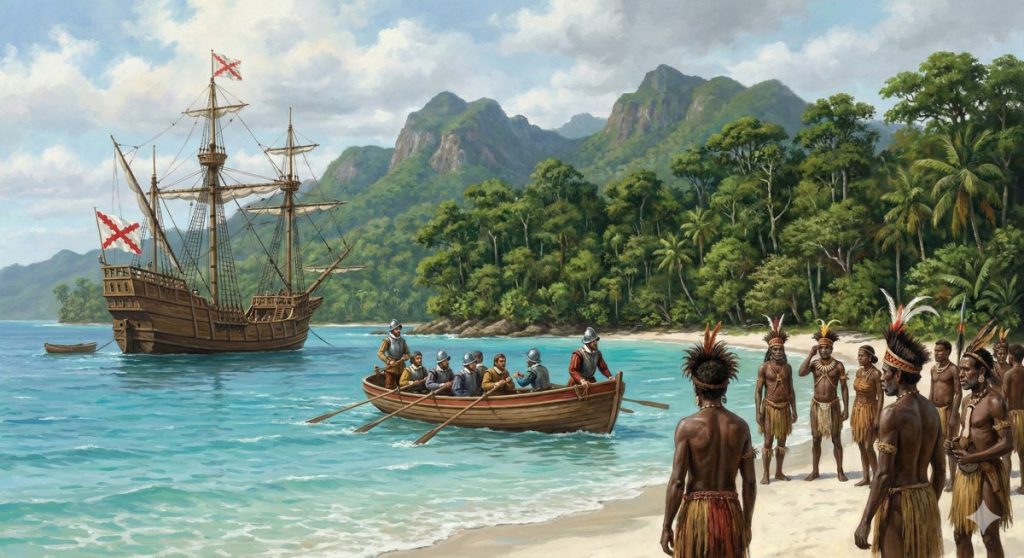

That same year, amidst the vast waves of the South Pacific, Spanish navigator Iñigo Ortíz de Retes was sailing from the Maluku Islands toward the Americas when he landed on a massive island. Observing that the locals’ skin tone resembled that of the Guinea blacks he had seen in West Africa, he officially named the island “New Guinea“.

Meanwhile, the human intellect was not sitting idly by.

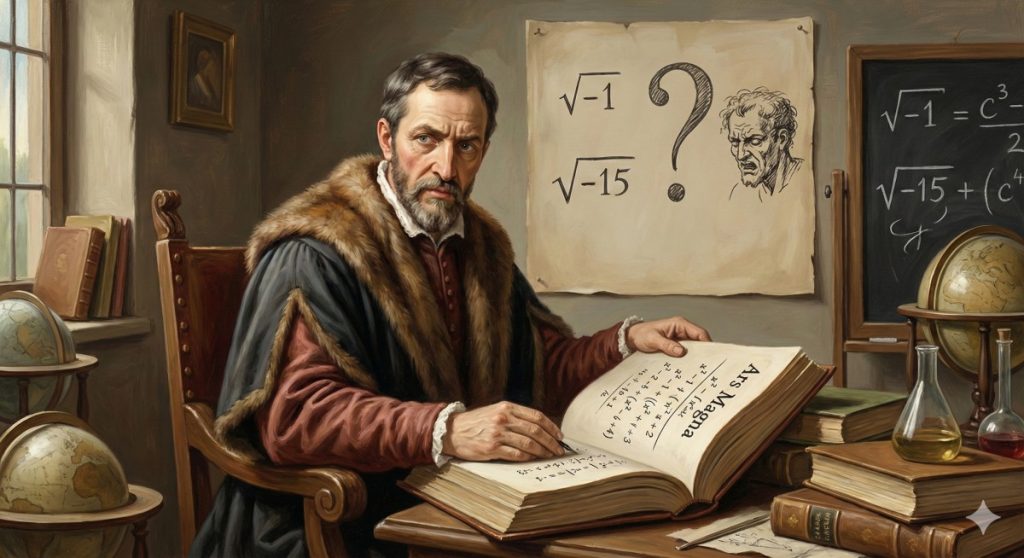

In Milan, Italy, a temperamental mathematician named Gerolamo Cardano published a book titled Ars Magna (The Great Art). This work systematically explained how to solve cubic and quartic equations. Even more revolutionary was his first brush with the concept of square roots of negative numbers during the solution process. This exploration, which he described as ‘mental torture,’ planted the seeds for the revolutions in physics and engineering that would follow centuries later.

In Padua, Italy, the world’s first university botanical garden broke ground. Its design was rich with symbolism: a circle representing the world, a square in the center representing the ocean, and four gates facing the four known continents.

Here, corn and tobacco from the Americas, spices from India, and exotic flora from Africa lived together. Scientists conducted research here, marking the early bud of modern plant taxonomy and pharmacology.

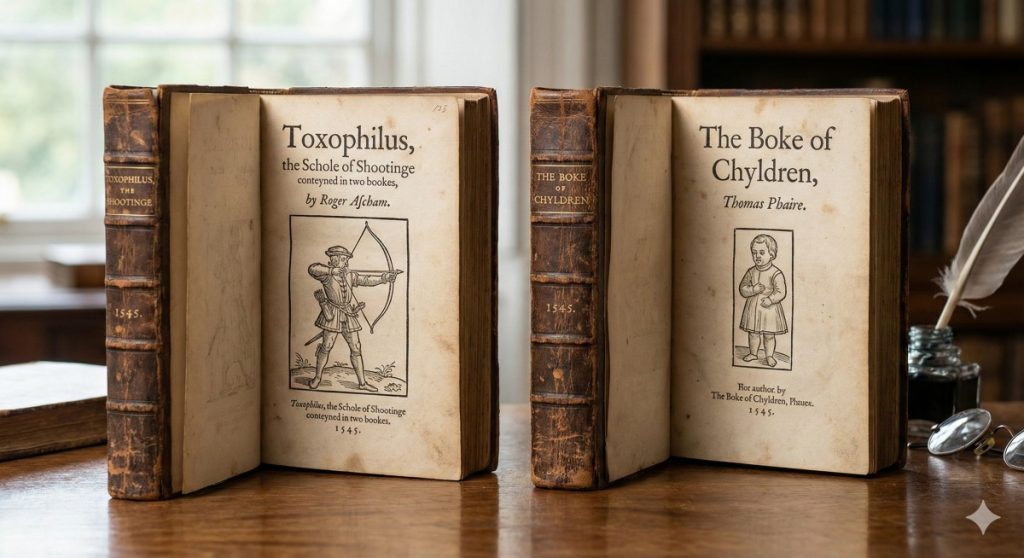

In England, two extremely important popular science books written in English were published this year: Toxophilus, a treatise on physical and military training by Roger Ascham, and The Boke of Chyldren, a pediatric work by Thomas Phaire. This signaled that authors were beginning to write in ‘plain, everyday language’ that the common people could understand. Waves of intellectual liberation were beginning to surge from these seemingly minor details.

Conclusion: A World Irrevocably Tied Together

The year 1545 shows us that the world had truly become interconnected. From the silver mines of the Andes to the sinking ships of the English Channel, from the Taoist elixirs in China to the night raids in Japan, every event was a thread in a single global tapestry. Humanity had reached a point of no return: The era of isolated development was over.