In the long river of history, the five years between 1535 and 1540 were more than just a continuation of colonial expansion following the Age of Discovery. They marked a period of violent labor pains as the global order transitioned from “wild growth” toward “institutionalized operation.”

As 1540 arrived, the Age of Sail began weaving a dense web across the globe. Yet, in this specific year, that web faced the harsh challenges of nature and the violent restructuring of human power, creating a historical coordinate defined by extreme thirst and relentless bloodshed.

1540 Global Power Struggle

Panic Under the Scorching Sun

For Europeans in 1540, it felt as though God had personally reached down and turned off the faucet. Hans Stolz, a winemaker from Alsace, recorded in his diary with terror that from February 10 to mid-June, hardly a drop of rain fell. The sun in April and May blazed with mid-summer intensity, causing cherry trees to bloom fully by early April.

As the rains vanished, mighty rivers—the Rhine, the Seine, the Elbe—dropped to historic lows. In the bed of the Suhre River, people dug five feet deep without finding a trace of water. Citizens in Basel joked grimly that one no longer needed a bridge or a boat to cross the Rhine; you could simply walk.

Worse than the thirst was the secondary collapse: watermills stopped turning, meaning grain could not be ground into flour, sending food prices into the stratosphere. Tainted water sources triggered massive outbreaks of dysentery. In this apocalyptic atmosphere, frequent urban fires led to a “Arsonist Panic”—a form of early mass hysteria where the public blamed vagrants and religious dissidents, claiming they were burning cities at the Devil’s command.

That year, Central Europe saw approximately 800,000 deaths from hunger, fire, and disease. Ironically, the extreme heat produced grapes with such high sugar content that the “Wine of 1540” became a legendary, expensive vintage—the only “blessing” left for the aristocracy in a landscape of hellish drought.

Awakening on the Printed Page

While the elites found their rewards even in the darkest times, a few flickers of rational light began to pierce the iron curtain of the era.

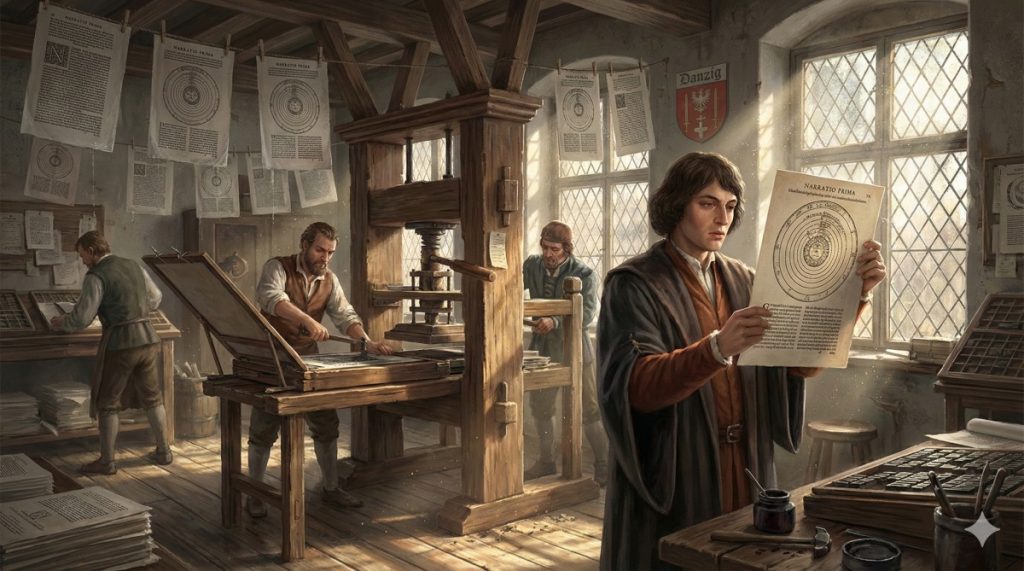

In Danzig, a young man named Georg Joachim Rheticus published a pamphlet titled Narratio Prima. It acted like a “trailer” for a blockbuster movie, dropping a bombshell on the academic world by publicly debuting Nicolaus Copernicus’s heliocentric theory.

This was not an isolated event. With breakthroughs in mathematics by Tartaglia and Cardano, and the application of geometry in navigation and fortification, humanity began to describe the world through logic and numbers.

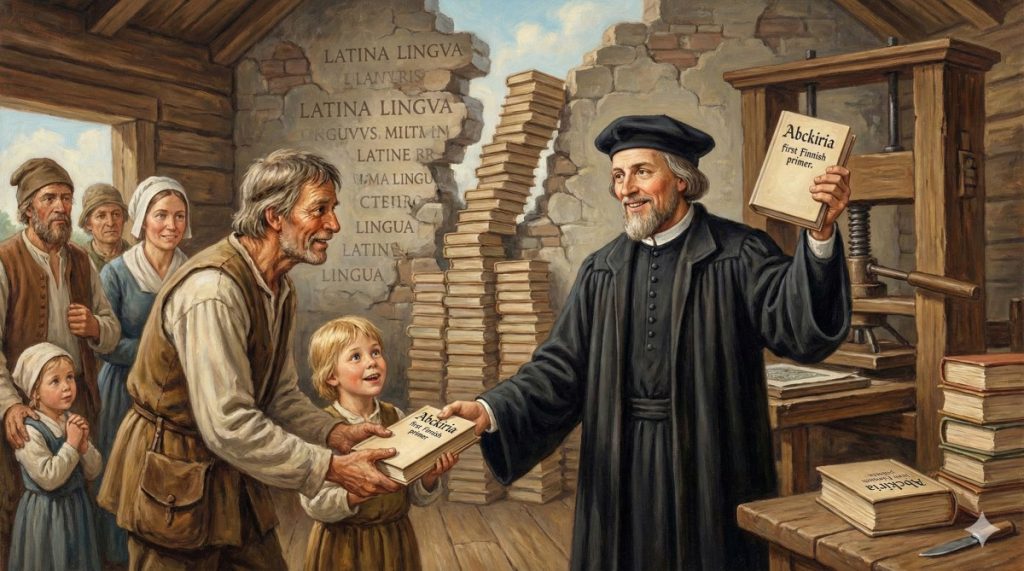

But faster than scientific truth was the awakening on paper. In England, the Great Bible was placed in every parish church.In Northern Europe, Mikael Agricola published the first Finnish primer, the Abc kiria, marking the birth of Finnish literature and national identity.

The high walls of Latin-guarded knowledge were being dismantled, brick by brick, by the “demolition crew” known as the printing press.

Cold Steel in London

While European commoners were clawing through dry riverbeds for a drop of water, the axes in the Tower of London were once again being polished to a mirror finish.

On July 28, 1540, the blade fell, taking the head of Thomas Cromwell. The executioner of five years ago had become the executed.

For a decade, Cromwell—Henry VIII’s most formidable lieutenant and a low-born legal genius—had operated like a precision machine. He single-handedly pried England away from the Pope’s grasp and made the King the supreme head of the English Church.Through the dissolution of the monasteries, he seized a millennium’s worth of ecclesiastical wealth and redistributed it to the Crown and the rising gentry.

Yet, a man of such stature was disposed of by the King in a heartbeat.The catalyst?

A 16th-century version of a “Tinder fail” where the “online” profile didn’t match the reality.

As the technical architect of the English Reformation, Cromwell had been searching the globe for allies to counter the powerful Habsburgs. He orchestrated a marriage between Henry VIII and Anne of Cleves.

Henry had seen a portrait by Hans Holbein and was filled with anticipation. However, when they finally met in person on New Year’s Day 1540 at Rochester, the King’s heart sank—the portrait had been “heavily photoshopped” by the artist’s brush.

In a twist of bitter irony, the legal instrument used to destroy him was the “Bill of Attainder”—the very weapon this legal genius had perfected to eliminate his own enemies. Now, the barrel of that gun was turned on him.

The King was furious, and the consequences were dire. He directed his entire wrath toward the matchmaker, Cromwell. Seizing the opening, the conservative faction—led by the Duke of Norfolk and Bishop Gardiner, who had long detested the upstart—pounced. they slapped him with charges of “treason” and “heresy.”

From his prison cell, in a desperate bid for his life, Cromwell personally drafted the testimony needed to annul the King’s marriage. It was a futile effort. Just 19 days after the marriage was officially dissolved, his head fell on Tower Hill.

Once Cromwell was gone, Henry VIII eventually cooled off and began to regret losing his “most faithful servant,” but there was no “undo” button for the executioner’s ax. Cromwell’s death marked a pivot from “idealistic reform” toward “absolute autocracy.” The Tudor dynasty had just slammed the gas pedal on the road toward centralized power.

A New Army in Rome

While the old Church was being smashed to pieces in England, a new and far more formidable religious force was receiving its official “business license” in Rome.

On September 27, 1540, Pope Paul III, with a decisive stroke of his pen, issued the papal bull Regimini militantis Ecclesiae, officially chartering the Society of Jesus (the Jesuits).

This was no ordinary religious order. Its founder, Ignatius of Loyola, was a former professional soldier, and he grafted the military’s strict discipline and absolute obedience onto the DNA of the organization. In addition to the standard vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience, Jesuit brothers took a unique fourth vow: Absolute obedience to the Pope.

What did this mean in practice?

It meant they were the Pope’s “Rapid Response Force.” Wherever the Pope pointed, they struck. Whether it was the furthest corners of the earth or the most dangerous “lion’s dens,” a Jesuit wouldn’t hesitate; they’d pack their bags and go. They were, in every sense, the “Soldiers of God.”

True to form, shortly after the order’s founding, a “hard-hitting” missionary named Francis Xavier set out from Goa, India, traveling all the way east to plant the Catholic flag on the shores of Japan.

But these men offered more than just strategic grit; they possessed a massive “IQ advantage.” They were masters of classical literature, theology, and the hard sciences—boasting both elite “hardware” (discipline) and “software” (intellect). From this moment on, Western civilization began exporting more than just commodities and gunpowder; it began exporting a highly systematic framework of faith and civilization. Using these integrated, modular systems, they began their conquest of the world.

Heroic Tears by the Ganges

While the West was beginning its systematic conquest of the world, let’s turn our lens to Asia.

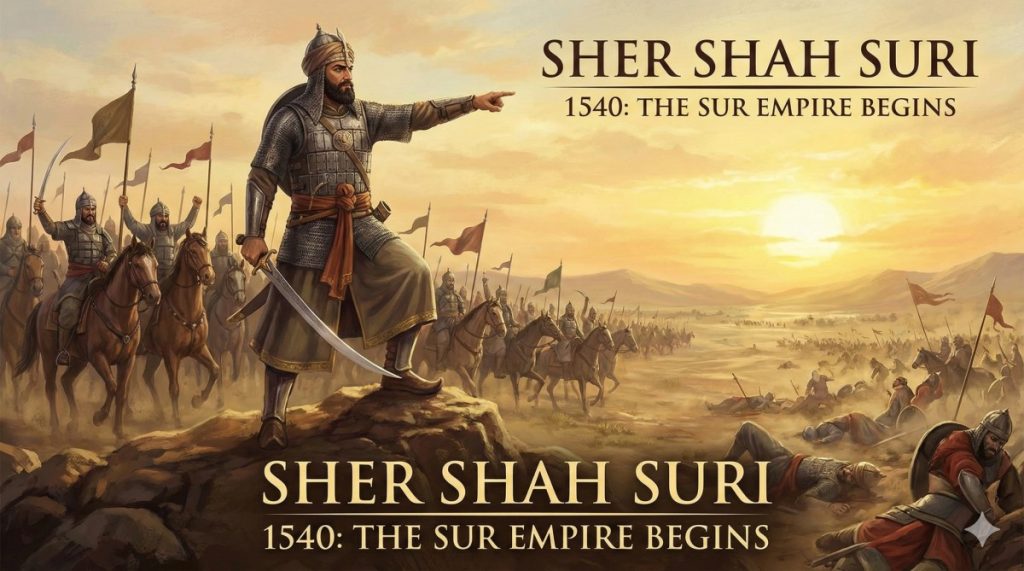

On May 17, 1540, the war drums thundered at Kanauj (also known as Bilgram) in Northern India.

The showdown featured Humayun, the second Mughal Emperor and son of Babur, against the Afghan strategist Sher Shah Suri. On paper, Humayun held a winning hand: an army of 50,000, including a high-tech artillery corps—the very same cannons his father had used to blast open the gates of India.

However, the Emperor had developed a “bad habit”—an addiction to opium. Under his hazy rule, the Mughal administration and military had completely deteriorated into a mess.

To make matters worse, Humayun chose to pitch his camp on low-lying ground right next to the Ganges. This poor choice turned into a death trap when a sudden, torrential downpour transformed the camp into a swamp.

His heavy cannons—the pride of his army—sank into the mud, becoming nothing more than expensive lawn ornaments.

Sher Shah seized the moment, commanding his cavalry to outflank and strike with surgical precision. The Mughal army panicked and shattered. Historical records describe Mughal generals tearing off their family crests and tossing them away just to escape unrecognized. Humayun himself only survived by leaping into the Ganges and swimming for his life.

With this single defeat, Humayun squandered almost the entire empire his father had built, beginning a fifteen-year life of exile that eventually led him to Persia. After seizing Delhi, Sher Shah founded the Sur Empire.

A true pragmatist, he launched currency reforms (promoting the Silver Rupee) and built the Grand Trunk Road. Though his dynasty was short-lived, his administrative blueprints essentially “laid the table” for the Mughal Empire’s eventual comeback.

Humayun’s exile wasn’t all bad news, however. By “hugging the leg” of the Persian Safavid Dynasty, he absorbed the richness of Persian culture. This cultural infusion would later set the stage for the peak of Mughal art and architecture under his son, Akbar the Great.

Growing Might Beyond the Great Wall

At the same moment in the Ming Empire, the Jiajing Emperor, Zhu Houcong, had successfully tamed the civil servant bureaucracy through early power struggles.

Now, he began his life as an “imperial shut-in” at the West Garden (Zhongnanhai). He had only two things on his mind: first, building a lavish, uniquely designed “double tomb” for his father in Hubei; and second, his obsession with Taoist alchemy and the pursuit of immortality.

To produce his elixirs, Jiajing forced palace maids into a cruel regime, feeding them only rainwater and mulberry leaves to produce specific biological “ingredients.” This horrific abuse created a reservoir of resentment within the Forbidden City that would soon boil over into the infamous “Palace Plot of the Year Renyin.”

Yet, beyond the Great Wall, a true threat was growing in the wild. Altan Khan, a descendant of the Golden Family and leader of the Tümed Mongols, had been recognized as the head of the right-wing tribes.

He established his base near modern-day Hohhot, attracting Han Chinese farmers and craftsmen fleeing taxes or famine. By building houses and temples and cultivating farmland, Altan Khan was transitioning from a mere nomadic chieftain into the founder of a “mixed agro-pastoral” state.

Altan Khan aggressively consolidated power, pushing rival tribes toward the east and seizing control of the vast region from Datong to the Hetao. His strategy toward the Ming transitioned from sporadic raids to organized pressure, repeatedly demanding “tribute and trade” (legalized border markets).

But the Jiajing Emperor remained behind closed doors, obsessed with his alchemy and flatly rejecting every request. He had no idea that a unified “Shadow Empire” of the steppes had formed right outside his doorstep. The Ming’s northern frontier was now hanging by a thread.

Blood in the New World

Leaving Asia, we cross the oceans to see what was happening in the Americas. This was the year the Spanish conquistadors’ dreams of gold reached their fever pitch—and the year those dreams began to shatter.

On February 23, 1540, Francisco Vázquez de Coronado set out from Mexico with a lavish expedition of over 300 Spanish elites and 1,000 indigenous allies. Their target: the legendary “Seven Cities of Cibola,” where streets were said to be lined with goldsmith shops and doorways encrusted with turquoise.

In July, they found it—but instead of golden cities, they saw only wretched little villages made of stone and mud. Heartbroken and starving, the Spaniards resorted to brute force, slaughtering, burning, and looting. A Zuni village that had existed for ages was wiped off the map in an instant.

While they found no gold, the expedition “failed upward” in a historical sense. Team member García López de Cárdenas became the first European to lay eyes on the Grand Canyon, and the party continued eastward to the Great Plains, encountering massive herds of American bison.

That same year, another conquistador, Hernando de Soto, was fighting for his life in the forests of the American Southeast. On October 18, in Mabila, Alabama, he fell into a trap set by Chief Tuskaloosa. The Spaniards barely escaped by burning the town to the ground. While thousands of indigenous people died, the Spaniards lost nearly all their supplies and the silver and pearls they had plundered along the way.

This battle served as a wake-up call: the dream of replicating the “easy” gold conquests of the Aztecs or Incas in North America was dead. The natives here were more dispersed, more resilient, and there was no pre-existing “tributary empire” for the Spanish to simply take over.

In South America, a grittier conqueror named Pedro de Valdivia led a tiny band of 150 men across the hyper-arid Atacama Desert to the fertile Mapocho Valley. He decided to dig in his heels there. This was the birth of modern Chile, marking the start of a 300-year bloody struggle between the Spanish and the local Mapuche people for control of the land.

Gunboats in the Red Sea

Meanwhile, a massive fleet was weighing anchor in the port of Goa, India. Led by Estêvão da Gama—son of the legendary Vasco da Gama—75 warships prepared to strike the Red Sea, aiming for the Ottoman Empire’s most vital naval base at Suez.

Ever since the elder Da Gama bypassed the Middle East to find the route to India, the Portuguese had acted like a surgical blade, cutting off the Ottoman “middleman” and shipping spices and silk directly to Lisbon.

But the Ottomans were no pushovers; they controlled the Red Sea and Persian Gulf, constantly threatening the Portuguese flank. The Portuguese goal was to smash the Ottoman presence in the Red Sea and seize the global spice trade for themselves.

As the clouds of war gathered over the Red Sea, the Emperor of Ethiopia, Dawit II, passed away in the mountains of East Africa. His successor, Galawdewos, took the throne in exile, surrounded by enemies. Seeing the Portuguese fleet roaming the Red Sea, he fired a desperate signal for help.

In the coming years, Portuguese musketeers and Ottoman artillery would wage a brutal proxy war on this ancient land. The battlefield for global supremacy had extended from the land to the vast oceans. The narrow Red Sea had become the most critical “line in the sand” on the global chessboard of two empires

By 1540, the “capillaries” of global trade were beginning to take shape. A surreal image emerged: while the European heartland was ravaged by drought and famine, the ports of Lisbon, Seville, and Antwerp were overflowing with treasures from across the globe—a “false prosperity” built on a worldwide network.